Remembering the Bitter with the Sweet

Click here to read the article in The San Diego Union-Tribune

Now that September is here, Mexicans on both sides of the border have been gearing up for the celebration of Mexico’s Day of Independence, a day that commemorates the country’s liberation from Spanish rule in 1821.

But before the fiesta gets underway, the papel picado hung, and the fireworks launched into the air, a moment of silence please, as we remember that September holds a bitter memory as well.

September is the month that Mexico lost its war with the United States.

A mere twenty-six years apart, these two events—gaining independence from Spain and surrendering to the US—are two of the most defining moments in Mexico’s history.

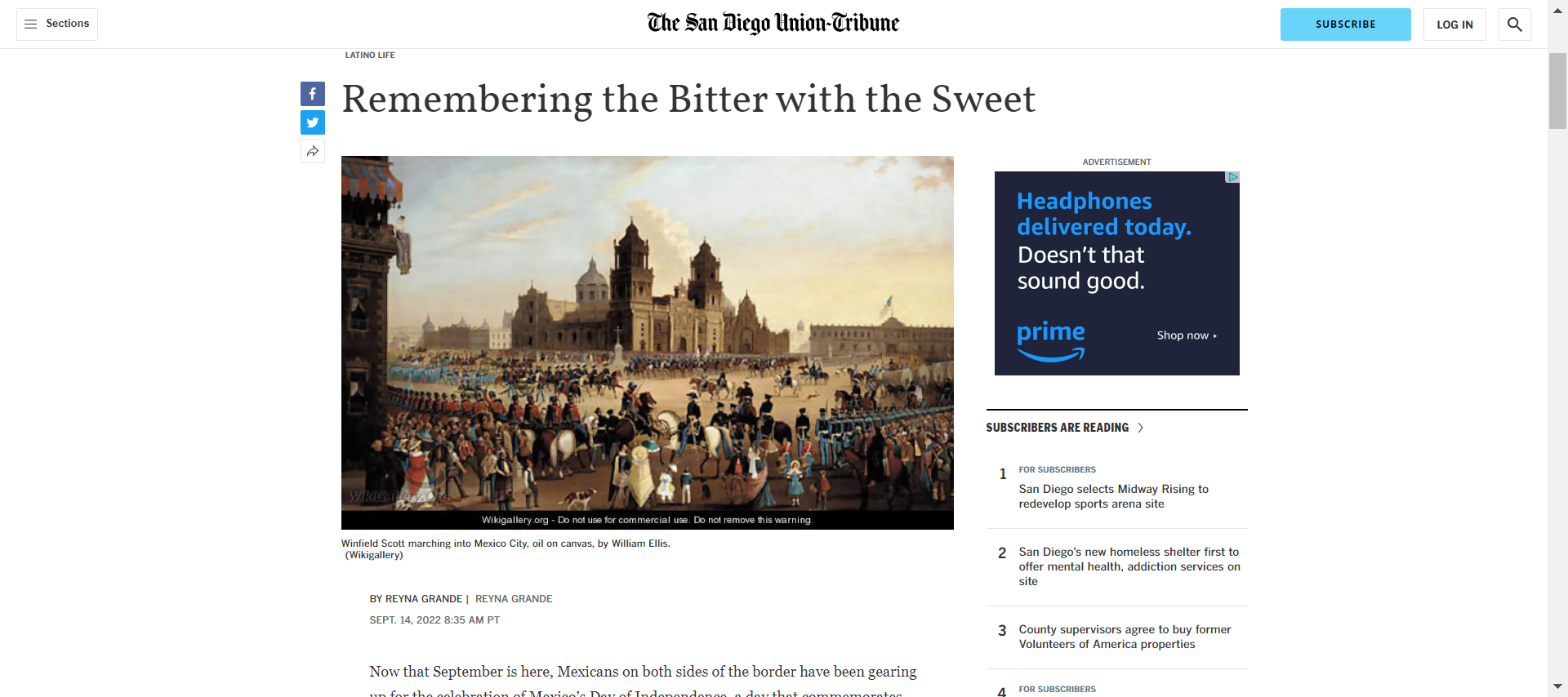

A hundred and seventy-five years ago, on September 14, 1847, on the eve of Mexican Independence Day, instead of celebrating the country’s freedom, Mexicans gathered in la Plaza de la Constitución (now known as El Zócalo) and watched in despair as General Winfield Scott and his troops entered the capital. After winning the last of the decisive battles against General Santa Anna, Scott triumphantly took possession of Mexico City. The Mexican people bearing witness that day saw their country fall once again into the hands of colonizers. As the American flag fluttered over the Palacio National, it demoralized the Mexican soul.

The US waged “a wicked war” on Mexico, as Ulysses S. Grant once said. “…One of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.”

Unsurprisingly, this defining moment in the history of both nations has been relegated to a mere footnote in the United States. Yet this war, or invasion, as it is called in Mexico, doubled the size of US territory and led to the fulfillment of what the US Government called Manifest Destiny. When President Polk dispatched his troops south to the Rio Grande, it was the first time the US invaded a sovereign nation. When Scott took possession of Mexico City, it was the first time the US occupied a foreign capital. The war led to the creation of the US-Mexico border as we know it today. It also set the stage for the American Civil War. Yet it is often glossed over in US history classes.

Not so in Mexico. Mexican children learn about “la invasión norteamericana” starting in elementary school.

One hundred and seventy-five years later, the consequences of the US invasion of Mexico can still be felt today by Mexicans on both sides of the border.

First, it turned Mexicans into victims of US imperialism, aggression, and greed. When the US made unsupported claims on the Rio Grande, and President Polk lied about Mexico shedding “American blood on American soil,” it bred ill will and distrust, setting a pattern that continues to complicate US-Mexico relations to this day.

With the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico was forced to accept the Rio Grande as its boundary. The border between the two nations became, as the great Chicana scholar Gloria Anzaldúa once wrote, “La herida abierta (the open wound), where the third world grates against the first and bleeds.”

The Mexicans living north of the boundary line woke to find themselves no longer in Mexico but in the US. They didn’t cross the border. The border crossed them. They became the first Mexican-Americans, perpetual foreigners in their own homeland.

The northern Mexican territory, which stretched to the Oregon border, was devoured by the United States, and Mexico became half the country it once was. From that moment on, the new map of Mexico would forever remind the Mexican people of their loss.

Ironically, it is now Mexicans who are often considered the invaders. When anti-immigrant groups use the term “invasion” to describe the humanitarian crisis at the southern border and the surge of Latino immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees, or when they put up billboards that read: “Stop the border invasion”—let us think for a moment and ask: Who invaded whom?

On September 14, 1847, the stars and stripes unfurled in the wind in full view of the city and to the sorrow of the Mexican people. Nevertheless, though Mexico might have lost half of its territory to the US, it held on to its freedom and has maintained its hard-fought independence. So, this September 15th, as the celebrations of the country’s biggest holiday get underway, let all on both sides of the border shout: “¡Viva Mexico!”

Reyna Grande is the author of A Ballad of Love and Glory/Corrido de amor y gloria, a historical novel that sheds light on the Mexican-American War. She will appear at Libélula Books & Co on October 3 and at San Diego City College on October 4.