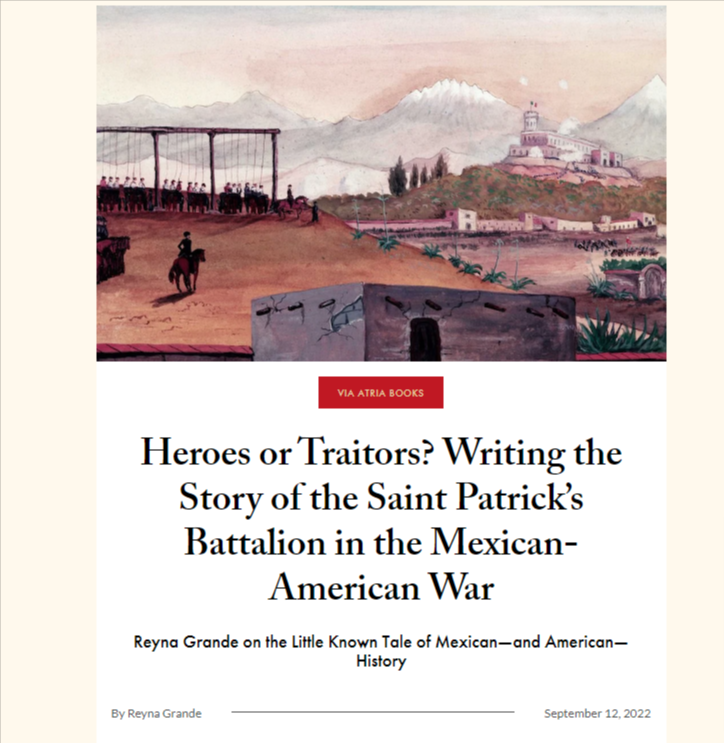

The Hanging of the San Patricios

Published in Lit Hub

They marched them all out of their prison, down the corridors where the sounds of their shuffling feet and dragging metal chains echoed against the damp walls. They took them outside and proceeded to San Jacinto Plaza in the heart of San Ángel. Daylight had broken, and the rain had ceased, but the cobblestones were wet and slippery beneath their feet. Riley held his head up but didn’t look at anyone. The square was full of people, even at this hour. Yankee soldiers stood around the perimeter, their faces filled with mockery and hatred, clearly looking forward to the grotesque spectacle that was about to unfold.

“God have pity on us,” Dalton said.

Riley turned his head at the sound of his friend’s voice and there, looming before him, were the gallows with sixteen nooses hanging down, swaying in the morning breeze. There was no platform, no trap-door. Eight wagons pulled by mules had been placed underneath the nooses, waiting.

“Courage, my brave brothers!” Riley said. “Courage!” But his own knees were already trembling…

–From A Ballad of Love and Glory

*

One hundred seventy-five years ago this week, on September 10-13, 1847, the largest hanging in United States history took place.

Over the course of those three days in Mexico City, fifty members of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion—known as the San Patricios—were hanged at the gallows on the orders of General Winfield Scott.

Who were the San Patricios?

Depending who you ask, they were either heroes or traitors.

*

At one of my book readings in 2013, someone asked me if I had heard of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, an artillery unit composed mainly of Irish soldiers who’d deserted the US Army and switched sides to fight for Mexico during the Mexican-American War. I had never heard of them. “You should write their story,” this person suggested to me.

I think most writers have had this experience when readers offer ideas for our next projects, but that doesn’t mean we will follow through on it. My immediate thought was that I could never write a book about soldiers, war, battles, politics, especially one set in the 19th century. I knew little about Mexican history much less Irish history.

Like most children in US schools, I was never taught about this war, or invasion, as it is called in Mexico. So out of curiosity, I googled the Saint Patrick’s Battalion and learned about these soldiers who had risked their lives to defend my native country. I became intrigued by their leader, John Riley, a 30-year-old immigrant from County Galway. Hungry to learn more of this history I was never taught, I read books by historians Peter Stevens (The Rogue’s March), Robert Miller (Shamrock and Sword), and Michael Hogan (The Irish Soldiers of Mexico).

My fascination grew as did my understanding about this war and the role the San Patricios played in it. I learned that almost half of the US Army was composed of foreign-born soldiers, 25% of them Irish, (and many German, Italian, Scottish, and Polish immigrants), most of them Catholic and poor. Due to the ethnic discrimination and religious prejudice they encountered in the US Army, and after suffering severe punishments and ridicule at the hands of nativist officers, some of these foreign soldiers deserted the US Army and swam south across the Rio Grande in search of something better on the other side.

On April 12, 1846, Private John Riley, in an act of defiance, threw himself into the Rio Grande and joined the Mexican ranks. Later that same year, Mexican president and general, Antonio López de Santa Anna, created the Saint Patrick’s Battalion with Riley as its leader.

Now fighting for a Catholic nation where he was treated as an equal and properly rewarded for his skills (he eventually rose to the rank of colonel), Riley had a banner made for his battalion. Though no physical banner exists now, we know what it looked like from a letter he later wrote from his prison cell. “It was that glorious Emblem of native rights, that being the banner which should have floated over our native Soil many years ago, it was St. Patrick, the Harp of Erin, the Shamrock upon a green field.”

Not much of Riley’s personal story is known since parish records in Ireland were destroyed in a fire. What is known is that he left a son behind in Ireland, and perhaps a wife. And that he sent money home to help his family survive the famine ravishing his homeland. This story was familiar to me. My own father had immigrated to the US, leaving his wife and three children behind in Mexico. He came to this country for the same reasons I imagined Riley had—to find a way to help his family escape grinding poverty and give them a better life.

In the 1840s, the Irish were the least desirable group of immigrants, dehumanized and reviled. Their white skin did not protect them from discrimination. They were treated with the same disdain that Latino immigrants suffer today. I realized I did have a personal connection to Riley, even if we came from different cultures and historical eras. And once I formed that bond with him, I could see that historical moment through his eyes.

So, one day, I wrote a scene from John Riley’s point of view. Then I wrote another.

Though initially I hadn’t considered following through on that reader’s suggestion that I write a book about the San Patricios—their story wouldn’t let me go. So, I embarked on a seven-year journey not only to tell the tragic but heroic story of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, but also to shed light on a forgotten moment in this country’s history—the US invasion of Mexico and the land-grab that doubled the size of the continental US.

*

On August 20, 1847, at the Battle of Churubusco, which was then the outskirts of Mexico City, the Saint Patrick’s Battalion fought bravely to their last bullet and cannon ball. Eighty-five of them were captured, including John Riley. At their court-martial, instead of facing the firing squad, as dictated by the Articles of War, most were sentenced to hang. Because he’d deserted a month before the US officially declared war on Mexico, John Riley’s sentence was reduced to fifty lashes and branding with the letter “D” for deserter on the cheek. Yet, when the time came, Riley was branded twice.

In the US, the soldiers of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion were viewed as traitors and renegades, but in Mexico, they were heroes and martyrs.

The US denied the existence of the battalion for several decades after the invasion. Perhaps it was to downplay the high number of desertions during the war, especially of the immigrants mistreated by nativist officers. Or perhaps it was to avoid drawing attention to the largest mass hanging in US history.

In contrast, Mexico has always honored the San Patricios with ceremonies and parades held in their honor in the month of September. If you go to Plaza San Jacinto, where the first hangings took place, you will find a bust of John Riley and a plaque listing the names of the fifty San Patricios who faced the gallows. And if you go to Riley’s hometown of Clifden, in County Galway, you will find a statue gifted to the city by the Mexican government.

The Mexican-American War has been called the war the US cannot remember and Mexico cannot forget. The consequences of it can still be felt today, especially at the US–Mexico border, which was drawn with blood and gunpowder.

The US waged “a wicked war” on Mexico, as Ulysses S. Grant once said. “…One of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.” But Mexico did have some unexpected allies—John Riley and the Saint Patrick’s Battalion—its Irish heroes.

A Ballad of Love and Glory, by Reyna Grande, is available now from Atria and forthcoming in Spanish from HarperCollins Español on October 4.